Liver Transplantation: Eligibility, Surgery, and Immunosuppression Explained

Jan, 14 2026

Jan, 14 2026

When your liver stops working, there’s no backup. No second chance. No pill that can fix it. For people with end-stage liver disease, a transplant isn’t just an option-it’s the only way to survive. And while the idea of getting a new liver sounds like science fiction, it’s now a routine, life-saving procedure for thousands every year. But it’s not simple. It’s not quick. And it doesn’t end when the surgery is over. Understanding liver transplantation means knowing who qualifies, what happens during surgery, and how the body learns to live with a foreign organ.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

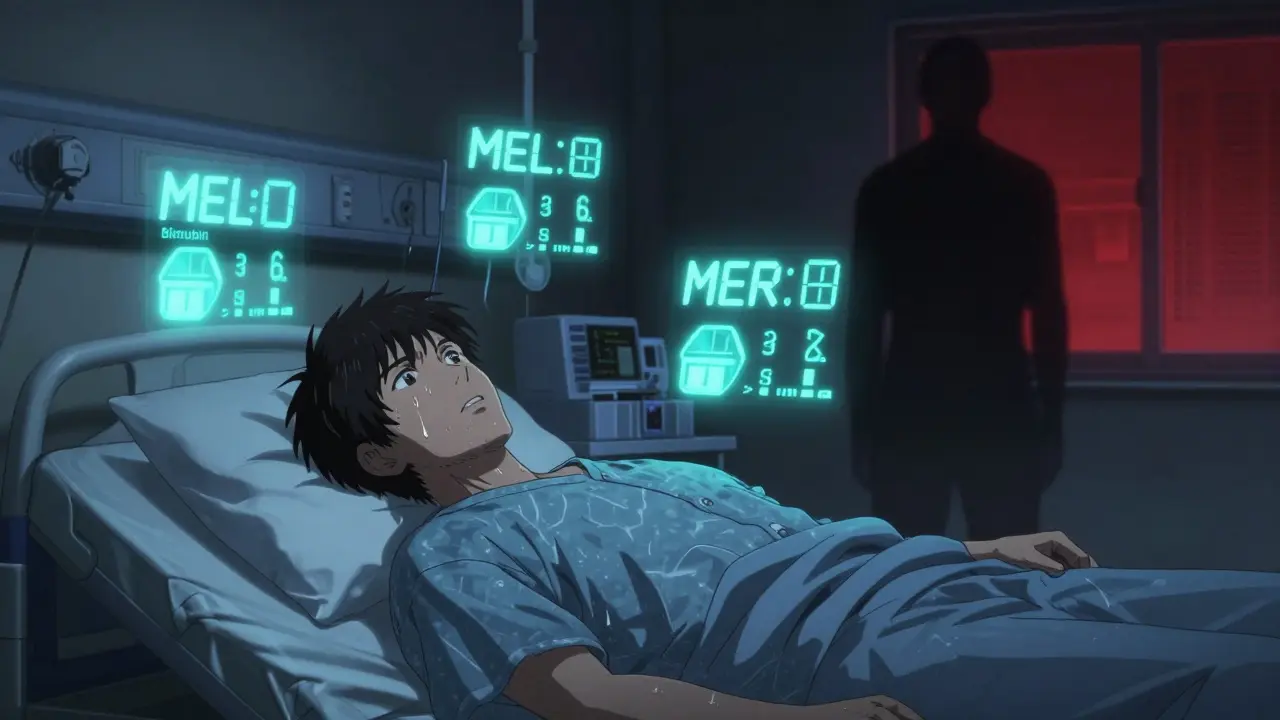

Not everyone with liver disease gets on the waiting list. The process starts with a full medical and psychological review at a transplant center. Doctors look at more than just how sick you are-they want to know if you’ll stick with the treatment after the transplant. That’s because a new liver won’t save you if you go back to drinking, skip your meds, or don’t show up for checkups. The main tool used to decide who gets priority is the MELD score. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The score ranges from 6 to 40. Higher numbers mean you’re sicker and closer to death. Someone with a MELD of 35 is in critical condition. Someone with a 10 might wait months or even years. In 2023, the MELD-Na system was updated to include sodium levels, helping people with fluid buildup get priority faster. There are strict rules about who’s disqualified. Active drug or alcohol use? You’re off the list. Metastatic cancer? No. Untreated heart or lung disease? Same. But there are exceptions. For liver cancer patients, the Milan criteria apply: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or has spread, you might still qualify if you get successful treatment first and your tumor shrinks. Psychosocial factors matter just as much. You need a support system. Stable housing. Reliable transportation. A team of doctors, social workers, and counselors evaluates whether you can handle the lifelong commitment. One patient in California shared how her transplant team helped her find housing and ride-share vouchers-things that made the difference between approval and denial.Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor: What’s the Difference?

Most livers come from deceased donors. But in some cases, a living person can donate part of their liver. It’s not common, but it’s growing. About 10% of transplants in the U.S. now use living donors. Why? Because the wait for a deceased donor liver can be long-up to 18 months in some states. A living donor can cut that to just a few months. Donors must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be in perfect health. No smoking, no drinking, no history of liver, heart, or kidney disease. The surgery removes 55-70% of the right lobe of the donor’s liver. That part regrows in about six to eight weeks. The donor’s remaining liver also grows back to full size. But it’s not risk-free. There’s a 0.2% chance a donor dies. About 20-30% have complications like infection, bile leaks, or blood clots. New guidelines are starting to change the rules. In 2023, the AASLD began allowing donors with controlled high blood pressure and BMIs up to 32. Some centers, like Columbia University, are even considering donors up to BMI 35 with careful screening. Their 5-year graft survival rate for these donors is 92%, higher than the national average. Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD donors are people whose hearts have stopped, but their organs are still viable. These livers have a higher risk of bile duct problems-25% compared to 15% for DBD livers. But new technology is helping. Machine perfusion, which keeps the liver alive and functioning outside the body, has cut those complications down to 18%. The FDA approved the first portable perfusion device in June 2023, extending liver preservation from 12 to 24 hours.What Happens During Liver Transplant Surgery?

The surgery takes between six and twelve hours. It’s done in three phases. First, the surgeon removes your damaged liver-this is called a hepatectomy. Then comes the anhepatic phase: you have no liver at all. Your body survives on machines that take over liver functions temporarily. Finally, the new liver is stitched in. Blood vessels and bile ducts are reconnected. Most surgeons use the “piggyback” technique, which leaves your inferior vena cava intact. This reduces bleeding and speeds recovery. After surgery, you go to the ICU. You’ll be on a ventilator for a day or two. Tubes will drain fluid from your belly. You’ll have a catheter and IV lines. The first five to seven days are the hardest. You’ll be tired, sore, and confused. Pain is managed, but you’ll still feel it. Most people stay in the hospital for 14 to 21 days if nothing goes wrong. The first sign of trouble? Fever above 100.4°F, yellowing skin, dark urine, or swelling in the belly. These could mean rejection or infection. You’ll be taught to recognize them before you leave the hospital.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Battle

Your body sees the new liver as an invader. Without drugs to stop it, your immune system will attack and destroy it. That’s why immunosuppression is non-negotiable. The standard starting regimen is triple therapy: tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Blood levels are checked weekly at first, then monthly. Doctors aim for 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lower it to 4-8 ng/mL. Too high? You risk kidney damage. Too low? Rejection kicks in. Mycophenolate stops white blood cells from multiplying. It causes stomach upset in 30% of patients and lowers blood counts in 10%. Prednisone, a steroid, reduces inflammation but causes weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss. That’s why many centers now use steroid-sparing protocols. In 2023, 45% of U.S. transplant centers stopped prednisone after the first month. The result? Diabetes rates dropped from 28% to 17%. About 15% of patients have acute rejection in the first year. It’s usually caught early with blood tests and treated by boosting tacrolimus or adding sirolimus. Long-term, 35% of patients develop kidney damage from tacrolimus. 25% get diabetes. 20% get tremors or headaches from neurotoxicity. You’ll need blood tests every week for three months, then every two weeks for six months, then monthly for a year. After that, quarterly. You’ll also need annual ultrasounds and liver biopsies if something looks off. Medications cost $25,000 to $30,000 a year-without complications. Insurance often denies coverage for pre-transplant tests. One survey found 32% of candidates were turned down for evaluations.Real Challenges and Changing Rules

The biggest controversy? The six-month sobriety rule for alcohol-related liver disease. Many centers require you to be sober for six months before listing. But a 2023 Yale study showed patients with three months of sobriety had the same 5-year survival rates as those with six. Critics say the rule is arbitrary and keeps people from getting help. Reddit threads like “6-month sobriety rule destroyed my chance at transplant” have hundreds of upvotes. People report wildly different rules across centers. Some will list you after three months if you’re in rehab. Others won’t budge. In British Columbia, a new 2025 policy now includes cultural support and community elders in the evaluation process for Indigenous patients, recognizing that recovery isn’t one-size-fits-all. Geographic inequality is another problem. If you live in California, you might wait 18 months for a liver. If you live in the Midwest, you might wait eight. The same MELD score can mean different wait times depending on your zip code.

What Comes After the Transplant?

Life after transplant isn’t a return to normal. It’s a new normal. You’ll take pills every day, forever. You’ll avoid crowds during flu season. You’ll wash your hands constantly. You’ll need to get vaccines for pneumonia, flu, and hepatitis A and B. You can eat normally again. Most people regain their energy. Many return to work. Some even run marathons. But you’ll never be “cured.” You’ll always be at risk for rejection, infection, or side effects from meds. Your liver can fail again, even after years. But here’s the truth: 85% of people are alive one year after transplant. 70% are alive five years later. That’s not just survival-it’s a second life. And for many, it’s worth every pill, every test, every fear.What’s Next for Liver Transplants?

Researchers are working on ways to eliminate immunosuppression entirely. Early trials at the University of Chicago show 25% of pediatric patients were able to stop all anti-rejection drugs by age five using regulatory T-cell therapy. If this works in adults, it could change everything. Artificial liver devices are improving, but none can replace a transplant for long-term survival. They’re useful as bridges-keeping people alive until a liver becomes available. The liver transplant market is growing fast, driven by rising cases of fatty liver disease. NASH, or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, now causes 18% of transplants-up from 3% in 2010. As obesity rates climb, so will the need for transplants. The future isn’t just about more livers. It’s about smarter ones. Better preservation. Personalized drugs. Less rejection. And more fairness in who gets access.Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to work, exercise, travel, and enjoy family life. But it’s not the same as before. You’ll take daily medications forever, avoid sick people, get regular blood tests, and watch for signs of rejection. You can’t drink alcohol or use drugs. But for many, this is a huge improvement over dying from liver failure.

How long does a transplanted liver last?

On average, a transplanted liver lasts 15-20 years. About 70% of recipients still have a working liver after five years. Some live 30+ years with the same transplant. Long-term success depends on following your medication schedule, avoiding alcohol, and managing conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

Is it possible to donate part of your liver more than once?

Technically, yes-but it’s extremely rare and strongly discouraged. The liver regrows, but each surgery carries risks. Most transplant centers won’t allow a second donation because the long-term effects aren’t fully known. Donors are carefully screened, and second donations are only considered in life-or-death situations with no other options.

What are the biggest risks after a liver transplant?

The biggest risks are rejection, infection, and side effects from immunosuppressants. Rejection happens in 15% of patients in the first year. Infections like pneumonia or urinary tract infections are common because your immune system is suppressed. Long-term, you’re at higher risk for kidney damage, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers. Regular monitoring helps catch these early.

Why do some people wait longer than others for a liver?

It depends on your MELD score, your location, and the availability of donors. Higher MELD scores get priority. But where you live matters too. In some regions, like California, there are fewer donors and more patients, so wait times are longer. In the Midwest, wait times are shorter. The system tries to be fair, but geography still plays a big role.

Can you get a liver transplant if you’ve had cancer before?

It depends. If you’ve had cancer that spread beyond the liver, you’re usually not eligible. But if you had liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) and it meets the Milan criteria, you can qualify. For other cancers, you typically need to be cancer-free for at least two years. Each case is reviewed individually by a transplant oncology team.

How do you know if your new liver is being rejected?

Signs include fever above 100.4°F, fatigue, nausea, dark urine, yellow skin or eyes (jaundice), and abdominal swelling. But often, rejection shows up first in blood tests-rising liver enzymes-before you feel anything. That’s why regular lab work is so important. If rejection is suspected, a liver biopsy confirms it. Most cases can be reversed if caught early.

Annie Choi

January 15, 2026 AT 23:37Just saw a living donor match go down in Vancouver last month-woman gave 60% of her liver to her brother who was MELD 38. He’s back at work in 10 weeks. No steroids after month one. Tacrolimus levels stabilized at 6.2. This isn’t sci-fi anymore-it’s daily medicine with a side of human courage.

And yeah, the six-month sobriety rule? Arbitrary. My cousin got listed at 90 days after rehab. Same survival stats. Stop punishing people for being sick.

Iona Jane

January 15, 2026 AT 23:50They’re lying about the survival rates. The FDA knows the perfusion machines are just delaying death. The organs are dying inside the box and they’re pretending they’re alive. You think they care about you? They’re just trying to sell you a 30k/year drug cocktail while the real cure-stem cell regeneration-is buried under patents held by Big Pharma. Wake up.

They’ll tell you you’re cured. You’re not. You’re a walking pharmacy.

Jaspreet Kaur Chana

January 17, 2026 AT 04:59In India we don’t have the luxury of MELD scores or machine perfusion. My uncle got a liver from a stranger who died in a bus accident-no paperwork, no waiting list, just a man who said ‘take it’ before he passed. We paid 2000 rupees for transport. No insurance. No legal team. Just faith and a prayer.

Now he runs a small tea stall. Drinks coconut water. No alcohol. No meds. Just God and turmeric. Maybe we’re doing it right in our own broken way.

Haley Graves

January 17, 2026 AT 14:30If you’re considering donation, stop romanticizing it. It’s not ‘the most generous act’-it’s major abdominal surgery with a 1 in 500 chance of death. The recovery is brutal. You’ll be in pain for months. Your body won’t feel like yours. And if the recipient rejects? You’re left with scars and guilt.

Don’t do it for the Instagram post. Do it because you’re ready to lose part of yourself-and you’re okay with that.

ellen adamina

January 19, 2026 AT 02:20Anyone else notice how no one talks about the mental toll? You get the liver, but the anxiety never leaves. Every stomach ache is rejection. Every headache is neurotoxicity. Every fever is death knocking.

I check my labs at 4 a.m. every Tuesday. I’ve memorized the normal ranges. I dream in AST and ALT. This isn’t a second life. It’s a constant vigil.

Tom Doan

January 20, 2026 AT 09:12So let me get this straight: we’re now approving donors with BMI 35 and controlled hypertension, yet we still require six months of sobriety for alcohol-related cirrhosis? The system isn’t medical-it’s moral theater. We’re not saving lives. We’re performing virtue.

And the fact that this is still debated in 2025? That’s the real tragedy.

Nishant Garg

January 22, 2026 AT 06:24Back home in Delhi, we have a phrase: ‘The liver remembers.’ It’s not just about the organ-it’s about the life you lived before. The nights you drank, the meals you skipped, the silence you kept.

Now you’re given a second chance. Not because you’re worthy. But because someone else died. That’s the weight you carry. Not the meds. Not the labs. The guilt.

So yes, you can run marathons. But you’ll never forget the shadow you’re running from.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 23, 2026 AT 12:21Y’all are acting like this is a miracle. It’s not. It’s a fucking industrial process. They harvest organs like commodities. They ration them by ZIP code. They turn people into MELD numbers. They profit off lifelong immunosuppressants. And you’re clapping like it’s charity?

It’s a system designed to keep you dependent. And you’re still thanking them for the scraps.

Jami Reynolds

January 24, 2026 AT 17:59According to the 2024 OPTN annual report, 78% of DCD livers in the U.S. are now preserved with machine perfusion. The 18% bile duct complication rate is statistically significant (p<0.01). However, long-term graft survival beyond 10 years remains uncorrelated with perfusion method. This contradicts the article’s claim of improved outcomes. Source: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/

Also, the 45% steroid-sparing rate is misleading-it excludes pediatric cases and non-DBD donors. The real number is closer to 31%.

Amy Ehinger

January 26, 2026 AT 05:40I got mine in 2021. Took me 14 months to wait. Got the liver from a guy who OD’d on fentanyl. I still think about him every day. Not in a sad way. In a ‘thank you’ way.

Now I walk my dog every morning. I eat pizza. I hug my kids. I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. I take my pills. And I don’t apologize for it.

It’s not perfect. But it’s mine. And I’m not done living yet.