Multiple System Atrophy: Understanding Parkinsonian Features and Prognosis

Nov, 14 2025

Nov, 14 2025

Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) is not Parkinson’s disease, even though it looks like it at first. Both cause slow movement, stiffness, and trouble balancing. But MSA is far more aggressive, affects more of the body, and doesn’t respond to the treatments that help Parkinson’s patients. If you or someone you know has been told they have parkinsonism but isn’t improving with levodopa, it’s worth asking: could this be MSA?

What Makes MSA Different from Parkinson’s?

MSA is a rare brain disorder that destroys nerve cells in multiple areas - the basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum. This isn’t just one region going bad. It’s a cascade. The hallmark of MSA is the buildup of a faulty protein called alpha-synuclein inside support cells in the brain, known as glial cells. These clumps, called glial cytoplasmic inclusions, are unique to MSA and not found in Parkinson’s disease.

While Parkinson’s mainly hits the substantia nigra and causes a classic resting tremor, MSA attacks the systems that control movement, balance, and automatic body functions like blood pressure, bladder control, and breathing. About 65-70% of MSA cases are the parkinsonian subtype, called MSA-P. That’s the version that mimics Parkinson’s most closely - but with key differences.

The Parkinsonian Features of MSA-P

People with MSA-P develop bradykinesia - slow, shuffling movements - and muscle rigidity that makes limbs feel stiff and hard to move. They often have trouble getting out of a chair or turning in bed. Speech becomes soft, slurred, or quivering. Facial expressions flatten into what doctors call a “masklike” appearance.

But here’s the catch: the tremor in MSA-P isn’t the slow, pill-rolling kind seen in Parkinson’s. It’s jerky, irregular, and happens mostly when holding a position - like reaching for a cup - not when the hand is resting. About 60% of MSA-P patients get this type of tremor, but it’s not the main driver of disability. The bigger problem is balance.

Within 1 to 2 years of symptoms starting, 85% of MSA-P patients fall. Not because they’re dizzy - though they often are - but because their body can’t adjust to sudden shifts in posture. One patient described it as “walking on ice you can’t feel.”

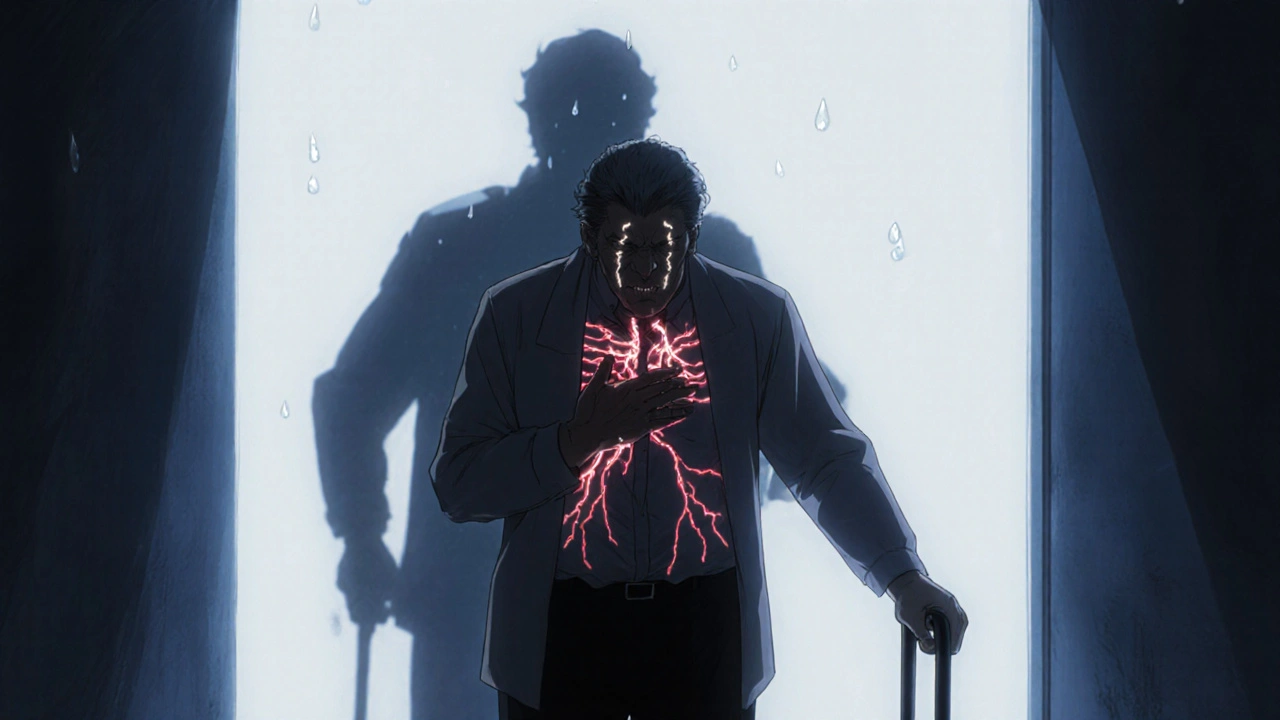

Autonomic Failure: The Silent Killer

The most telling sign of MSA isn’t the tremor or stiffness. It’s the autonomic failure - the breakdown of the body’s automatic systems. This is what separates MSA from Parkinson’s and why it’s so dangerous.

Nearly everyone with MSA has orthostatic hypotension - a sudden drop in blood pressure when standing. A drop of 30 mmHg systolic or 15 mmHg diastolic within three minutes is diagnostic. This causes fainting, dizziness, and blurred vision. About 75-80% of patients experience syncope. Some lose consciousness multiple times a day.

Bladder problems hit 85-90% of patients. Urgency, frequency, and incontinence are common. For men, erectile dysfunction is often the first symptom - appearing years before movement issues. One man reported losing sexual function at 48, was told it was “stress,” and didn’t get diagnosed with MSA until he started falling at 52.

Sleep is another battleground. Eighty to ninety percent have REM sleep behavior disorder - acting out dreams, yelling, kicking. Sixty to seventy percent also have sleep apnea, which worsens daytime fatigue and raises the risk of sudden death.

Temperature control fails too. Half of patients stop sweating in patches - their arms might sweat, but their legs stay dry. This makes overheating dangerous, especially in summer.

Why Levodopa Doesn’t Work - And What It Means

Doctors often start MSA patients on levodopa, the main drug for Parkinson’s. But here’s the hard truth: only 15-30% of MSA-P patients get any real benefit. And even then, it lasts maybe a year or two before fading. If someone’s symptoms don’t improve after 3-6 months on high-dose levodopa (up to 1,000 mg/day), MSA becomes much more likely.

This poor response isn’t just a treatment issue - it’s a prognosis clue. Patients who get no benefit from levodopa live, on average, 6.2 years after diagnosis. Those who do respond live closer to 9.8 years. That’s a huge gap in a disease where every month counts.

How Fast Does MSA Progress?

MSA-P moves fast. Most people need a cane within 3.5 years. By 5.3 years, they’re in a wheelchair. Within five years of symptom onset, half have lost most of their motor skills. Compare that to Parkinson’s, where many live independently for 15-20 years.

Median survival from first symptom is 6 to 10 years. The 5-year survival rate is between 52% and 68%. By 10 years, only 9-23% are still alive. The most common causes of death? Respiratory infections (45%), sudden cardiac events (20%), and aspiration pneumonia from swallowing problems (15%).

MSA-P declines faster than MSA-C (the cerebellar type). MSA-P patients reach the most advanced stage - bedridden - in about 5.7 years. MSA-C takes nearly 3 years longer.

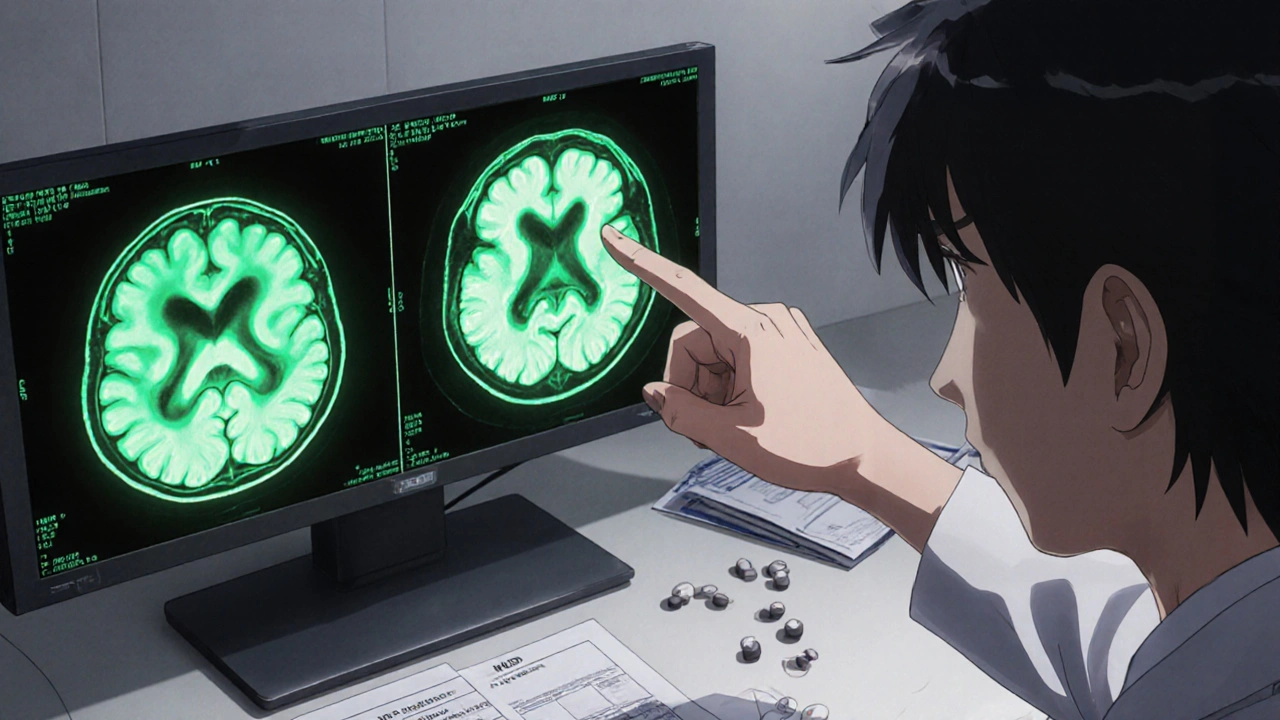

Diagnosis: The Long Road to Clarity

Getting diagnosed with MSA is hard. Early symptoms - dizziness, urinary issues, voice changes - are vague. Many are misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s, essential tremor, or even anxiety. Even neurologists can’t tell the difference until symptoms have progressed.

Diagnostic accuracy jumps to 85-90% only after 3-5 years. Key clues include: autonomic failure within 3 years of motor symptoms, poor levodopa response, and specific MRI findings. The “hot cross bun” sign - a cross-shaped pattern in the brainstem - appears in 50-80% of MSA-C cases. Putaminal atrophy and hyperintensity on MRI are common in MSA-P.

Emerging biomarkers are helping. Blood tests for neurofilament light chain - a protein released when nerves die - are 3 to 5 times higher in MSA than in healthy people. New research aims to combine MRI scans, blood markers, and autonomic tests to diagnose MSA within a year of onset. A large study expected in mid-2024 could change that.

Current Treatment: Managing Symptoms, Not Stopping the Disease

There’s no cure. No drug slows MSA. Treatment is all about managing symptoms and keeping people safe.

For low blood pressure: fludrocortisone, midodrine, or droxidopa are used. These help raise standing blood pressure but can cause high pressure when lying down - a dangerous trade-off.

For bladder issues: anticholinergics, catheterization, or botulinum toxin injections may be used. For sleep apnea: CPAP machines. For REM sleep behavior disorder: clonazepam or melatonin.

Physical therapy helps maintain mobility as long as possible. Speech therapy addresses swallowing risks - a major cause of death. Dietitians may recommend thickened liquids and soft foods.

Recent drug trials targeting alpha-synuclein have failed. The PASADENA trial showed only a tiny, clinically meaningless delay in progression. As of late 2023, only three active clinical trials worldwide are trying to find a disease-modifying therapy.

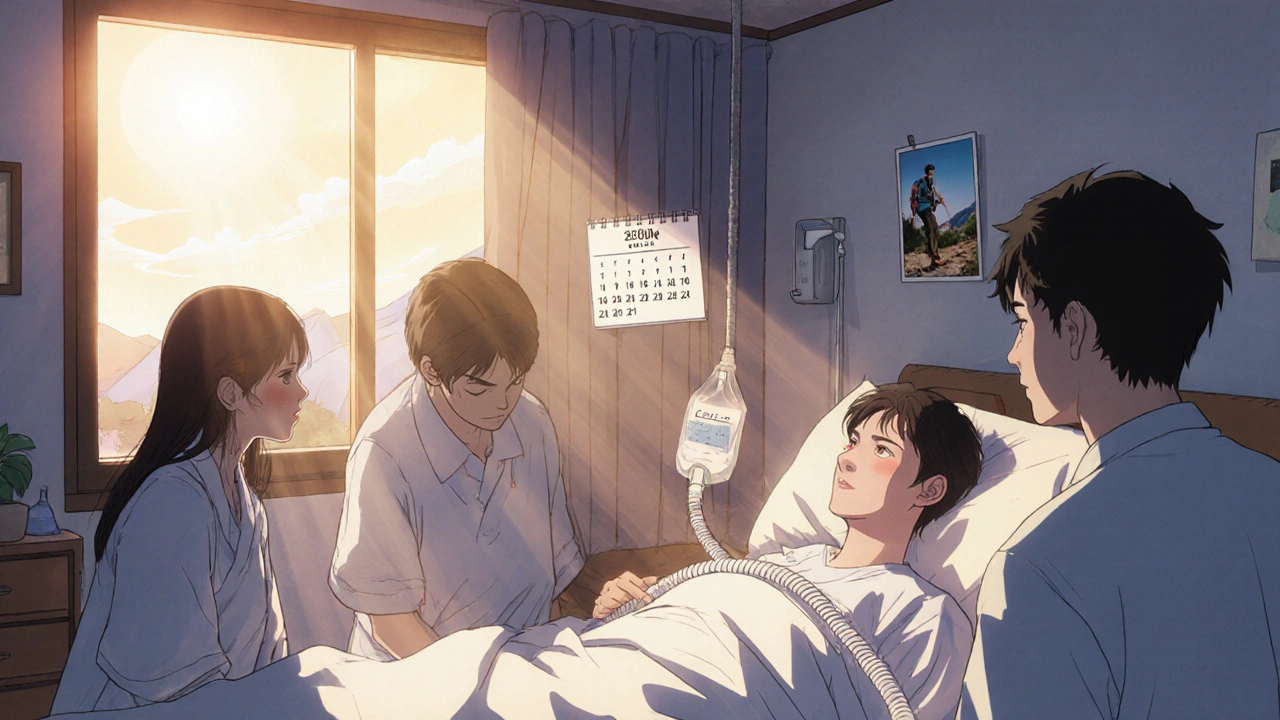

Living With MSA: The Human Cost

Quality of life plummets fast. A 2021 survey of 327 MSA patients found 78% rated their quality of life as “poor” or “very poor” within four years of diagnosis. In Parkinson’s, that number is 35% at the same stage.

Patients describe the terror of rapid decline. One woman, diagnosed at 55, said: “I lost my independence faster than I lost my hair. I went from hiking to needing help to pee in six months.”

Family caregivers face burnout. The need for 24/7 care, constant monitoring for falls and choking, and the emotional toll of watching someone deteriorate quickly is overwhelming.

Support groups - like the MSA Coalition with over 12,500 members - are lifelines. They offer practical advice, emotional support, and updates on research.

What’s Next for MSA Research?

Dr. Lucy Norcliffe-Kaufmann of NYU says it best: “By the time motor symptoms appear, 50-70% of the neurons are already gone.” That’s why early diagnosis is the biggest unmet need.

Researchers are now looking at blood tests, spinal fluid markers, and advanced imaging to catch MSA before it’s too late. If we can diagnose it at the pre-symptomatic stage - when the damage is still reversible - we might finally have a shot at stopping it.

Until then, the prognosis remains grim. Most patients won’t live beyond a decade. But better symptom care, earlier diagnosis, and stronger support systems can make those years more dignified - and less lonely.

Is MSA the same as Parkinson’s disease?

No. While MSA shares symptoms like slowness and stiffness with Parkinson’s, it affects more brain areas, causes severe autonomic failure early on, and doesn’t respond well to levodopa. MSA progresses faster and has a much shorter life expectancy.

Can MSA be cured?

No cure exists today. Treatments only manage symptoms - like low blood pressure, bladder issues, and sleep problems. No drug has been proven to slow or stop the disease progression.

How long do people live after being diagnosed with MSA-P?

Median survival is 6 to 10 years from symptom onset. About half of patients lose most motor function within five years. The 10-year survival rate is only 9-23%.

Why does MSA cause fainting?

MSA damages the nerves that control blood pressure. When standing, the body can’t tighten blood vessels fast enough, causing a sudden drop in pressure - called orthostatic hypotension. This leads to dizziness, blurred vision, and fainting.

Is MSA hereditary?

No. MSA is not inherited. It’s a sporadic disorder, meaning it occurs randomly without a known genetic cause. Family members are not at increased risk.

What’s the best way to improve quality of life with MSA?

A multidisciplinary team is key: neurologist, physical therapist, speech therapist, urologist, and palliative care specialist. Managing blood pressure, preventing falls, using feeding tubes if swallowing fails, and addressing sleep issues can extend comfort and independence. Support groups also help reduce isolation.

Latrisha M.

November 14, 2025 AT 17:03MSA is one of those diseases that slips through the cracks because it mimics Parkinson’s too well. I’ve seen patients go years without a proper diagnosis because doctors default to the common diagnosis. The autonomic symptoms are the real red flags - if someone’s fainting regularly or has unexplained urinary issues before motor problems, push for MSA testing. Early recognition changes everything for care planning.

Melanie Taylor

November 16, 2025 AT 13:13This hit me hard. My aunt was misdiagnosed for 3 years. They thought it was stress-induced tremors. By the time they caught MSA, she couldn’t stand without help. The worst part? No one warned us how fast it’d take her voice, then her bladder, then her ability to swallow. I wish this post had existed back then.

Daniel Stewart

November 17, 2025 AT 13:11It’s fascinating how the body’s autonomic nervous system - that silent, unseen conductor of life - gets obliterated in MSA. We treat symptoms like broken cogs, but the entire orchestra is collapsing. The real tragedy isn’t the motor decline; it’s the erasure of the body’s unconscious harmony. We don’t cure death. We just learn to listen for its rhythm sooner.

John Mwalwala

November 17, 2025 AT 18:53Let me break this down with the real science: alpha-synuclein glial inclusions = MSA. Lewy bodies = Parkinson’s. Different cell types, different pathways. But here’s what Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know - they’ve been dumping billions into Parkinson’s drugs because the market is bigger. MSA gets crumbs because it’s rare. That’s why the trials fail - they’re testing Parkinson’s meds on a different disease entirely.

Deepak Mishra

November 19, 2025 AT 09:14OMG this is so true!!! I had a cousin who was like ‘I can’t feel my legs’ and they told him it was sciatica 😭 then he fell 4 times in a week and they finally did the MRI and it was MSA-P… he died in 5 years 😭 I’m crying rn… someone pls help us 😭

Diane Tomaszewski

November 20, 2025 AT 06:40I think what’s missing here is how lonely this disease makes people feel. It’s not just the physical decline - it’s knowing no one else understands what you’re going through. Even family starts to look away after a while. The support groups aren’t just helpful, they’re necessary. They’re the only place where you don’t have to explain what ‘autonomic failure’ means.

Teresa Smith

November 21, 2025 AT 23:59As a neurologist with over 18 years in movement disorders, I’ve seen too many MSA cases misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s or essential tremor. The key is timing: if autonomic dysfunction appears within three years of motor onset, MSA is highly likely. We need standardized protocols for primary care - not just referrals to specialists after years of mismanagement. This disease demands early, aggressive diagnostic pathways.

David Rooksby

November 23, 2025 AT 18:50Okay so here’s the thing - if you think this is bad, wait till you hear about the real conspiracy. The NIH has known about the alpha-synuclein glial inclusions since the 90s. But they’ve been burying the data because if MSA is proven to be a separate disease with its own pathology, then all those Parkinson’s drug patents? Worthless. Pharma doesn’t want you to know that levodopa doesn’t work because it’s targeting the wrong cells. They’d rather keep prescribing it and collecting insurance payments. The ‘hot cross bun’ sign? Been known since 1998. Why isn’t it in every neurology residency? Coincidence? I think not.

Rachel Wusowicz

November 24, 2025 AT 10:03...and yet... they still won't tell you... that the real reason MSA progresses so fast... is because... the blood-brain barrier... is actively... rejecting... any potential therapy... because... it's been... hijacked... by... the same... prion-like... mechanism... that... spreads... the... alpha-synuclein... in... glial cells... and... they... won't... test... anti-prion... drugs... because... they're... too... expensive... and... the... patient... pool... is... too... small... to... justify... the... trial... costs... and... the... FDA... won't... approve... orphan... drugs... unless... they... show... 20%... improvement... which... is... impossible... when... 70%... of... your... neurons... are... already... gone... by... diagnosis... and... the... trials... are... designed... by... people... who... have... never... held... a... dying... patient's... hand... at... 3am... when... their... breathing... stops... and... you... have... to... decide... whether... to... call... code... or... let... them... go... in... peace... and... nobody... talks... about... that... part... do they?... no... they don't...

ZAK SCHADER

November 24, 2025 AT 17:22Why are we wasting money on this? We got real problems in America - inflation, border security, school shootings. Why are we funding some rare brain disease that only affects a few thousand people? We should be helping real Americans, not some foreign medical research project. If you got MSA, tough luck. Life’s not fair.

Danish dan iwan Adventure

November 25, 2025 AT 11:14MSA-P: Alpha-synuclein glial inclusions. No levodopa response. Autonomic failure within 3 years. Median survival: 7.5 years. Prognosis: Terminal. No cure. End.

Oyejobi Olufemi

November 26, 2025 AT 23:17Let me tell you something - this isn’t even the worst part. The worst part is that MSA patients are often abandoned by their families because they’re ‘too much work.’ And the medical system? It’s designed to discharge you as fast as possible. They don’t care about quality of life - they care about bed turnover. And don’t get me started on how insurance denies CPAP machines because ‘it’s not a primary condition.’ This isn’t medicine - it’s a corporate death sentence dressed in white coats.

Dan Angles

November 27, 2025 AT 09:16As a caregiver for a patient diagnosed with MSA-P in 2021, I can confirm the clinical observations in this post are accurate. The multidisciplinary approach - neurology, palliative care, physical therapy, and speech pathology - is not optional. It is essential. We implemented a fall-prevention protocol, a modified diet with thickened liquids, scheduled toileting, and a bedside suction unit. These are not luxuries. They are survival tools. The emotional toll on caregivers is immense, but structured support and education reduce burnout significantly. I urge all clinicians to provide not just diagnosis, but a comprehensive care roadmap.

Ankit Right-hand for this but 2 qty HK 21

November 28, 2025 AT 04:06Look, I’ve read this whole thing and I’m just gonna say it - this is just another way for Western medicine to profit off of fear. In India, we treat these kinds of conditions with yoga, ayurveda, and spiritual healing. You don’t need MRIs and levodopa. You need inner balance. This whole post is just fear-mongering designed to sell more tests and drugs. People in the West are too obsessed with technology. We’ve lost touch with nature.

Jamie Watts

November 28, 2025 AT 09:39My wife was diagnosed with MSA-P in 2020. She responded to levodopa for 11 months. Then, nothing. She fell in the shower last week. We’re on hospice now. I wish I’d known how fast it would go. I wish I’d known about the sleep apnea and the swallowing risks. I wish someone had told me to get the feeding tube before she choked. This post? It’s the one I needed five years ago.